'He thought I was the one person in the world he could trust - the one person he could turn to or talk to.'

Neil Woods is a quiet and unassuming man, but for 14 years he worked as an undercover police officer infiltrating some of the country's deadliest organised crime gangs.

Murder, torture and intimidation were - and still are - a daily occurrence in Britain's gritty underworld.

From 1993 to 2007, Woods infiltrated groups such as Nottingham's Gunn Gang and The Burger Bar Boys, a ruthless county lines cartel operating between Birmingham and Northampton.

One of the few ex-undercover police officers to shun anonymity and go public with his experiences, over time Woods grew disillusioned with his work.

He thinks the war on drugs has failed. He believes his work as an undercover police officer contributed to a rise in gang violence, instead of tackling it.

Woods says drugs policy needs a complete overhaul if organised crime is to be brought down for good.

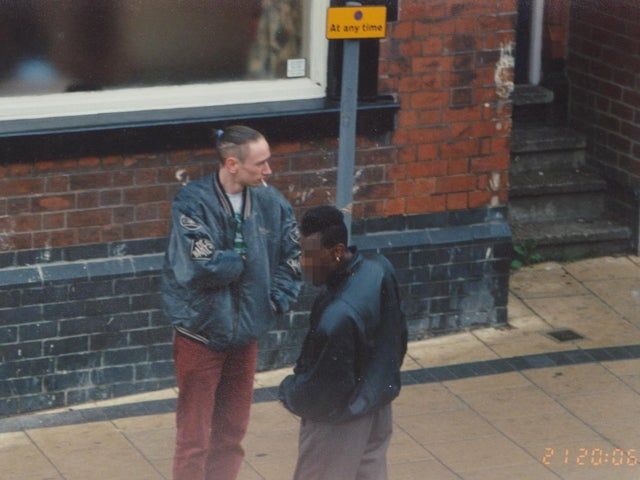

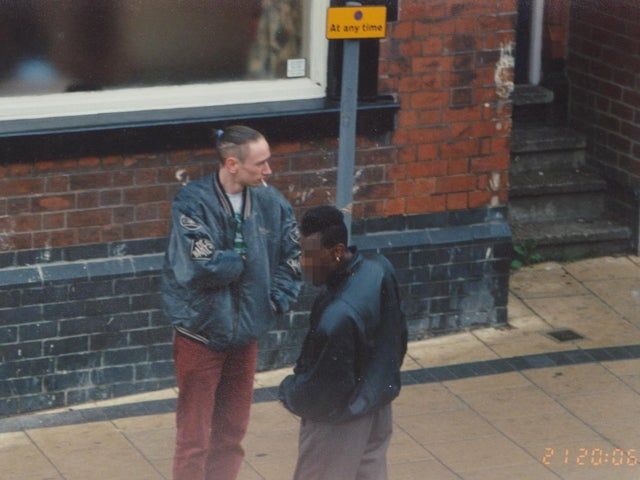

[caption id="attachment_255885" align="alignnone" width="259"]

Surveillance photograph of Neil Woods as an undercover police officer, c. 1995.

Surveillance photograph of Neil Woods as an undercover police officer, c. 1995.[/caption]

JOE: How did you become an undercover police officer?

Woods: By accident, really. When I started in the police, I was fairly crap at it and I almost lost my job several times. But I hung on in there, and after about four years as a uniformed constable, I managed to get an attachment to the drug squad.

Why did they ask you to join the drug squad?

There was a huge moral panic in the UK about crack cocaine. There'd been a huge moral panic about crack for years - before we actually had any on the streets of the UK. That's because all of the tabloid newspapers were constantly publishing stories about how crack was destroying America.

There was a push from the government to the police to make drugs like crack cocaine and heroin a priority. The police in Derbyshire then decided to give some young officers like myself an attachment to the drug squad.

What sort of disguises did you take on?

Well, in no time at all I realised that the people around me were the people who were homeless or verging on homeless - or those who lived or hung around in squats. People who were really on the fringes of society.

In the early days, I used to dress as a travelling 'scally'. Northern people will know that term. It's essentially a travelling thief. To look that way, I'd wear trainers and a full tracksuit.

I found that if I looked like these people, I had many more doors open to me. These people tended to be the most problematic drug users, and they would be connected to all the gangsters I needed to get evidence from.

How did you feed information you'd gathered back to the police? Was it a case of using cameras and listening devices?

When I started on a long-term operation, I didn't wear any sort of tech as I was likely to get searched. I would only ever wear tech once I was pretty confident that I'd won people over.

Then, I'd use all sorts of evidence and tech - small cameras, a doughnut (a device you attach to a phone to record phone calls), some audio devices, and sometimes a surveillance team would go on to photograph me somewhere.

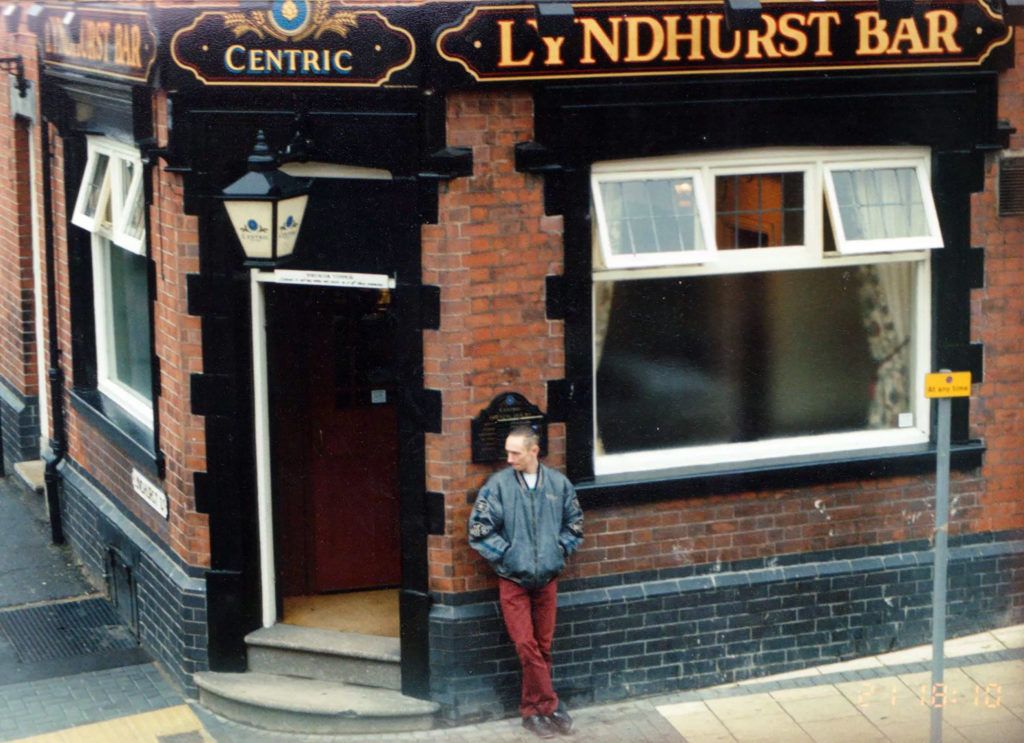

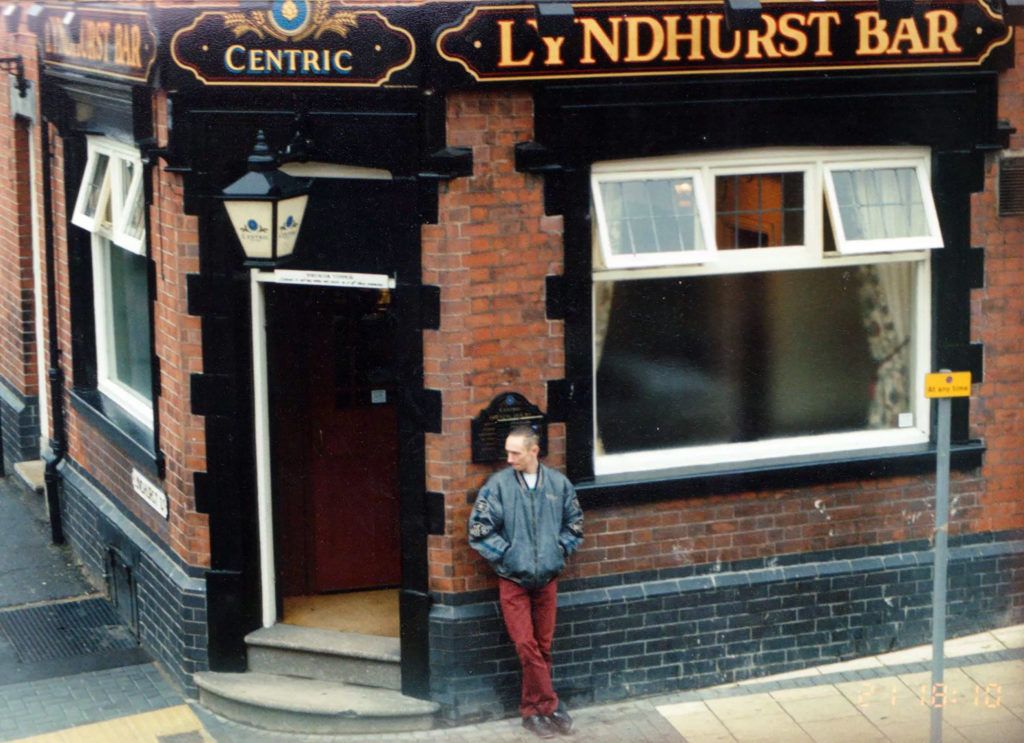

[caption id="attachment_255884" align="alignnone" width="176"]

More surveillance footage, c. 1995

More surveillance footage, c. 1995[/caption]

Was there a time you genuinely feared for your life?

Times when I thought I was genuinely going to die? Loads of times, to be honest.

One of the most dramatic ones was in 2001, in Leicester. I bought heroin from this gangster about four months before, but we didn't have any camera footage of him.

He wasn't coming out to deal, only sending runners. So I tempted him out by offering him a load of counterfeit Stone Island jackets. He was really keen to look at those.

He brought a couple of other gangsters with him. We met in this secluded car park.

After looking at the jackets, he said:

'Did you just want to sell me these, or are you after something?'

I thought that if I bought crack off him, he'd get more time in prison. So I said

'I'll have 20 white off you if you're carrying.'

So he's there, cutting up this massive block of crack. But while he's doing that, one of his two mates looks really suspiciously at me, pushes me up against this fence and then starts feeling my clothes.

He found it, didn't he. He found the camera. It was a little metal button on my shirt.

I slowly backed away while his mate was shouting

'He's Five-O! He's f***ing heat man!'

He replied

'Don't worry about my mate, he's a dickhead.'

I agreed that he was a dickhead, and made off with the drugs.

But by the time I'd made it to the car park exit, he was back in the car. His mate must have told him exactly what happened, because I heard the wheels screeching on the car, coming towards me.

The car zoomed towards me as I was running down the pavement. It mounted the pavement. I'm sprinting for my life.

Luckily, we came up to a roundabout - and there were metal railings to protect the footpath. I'd just managed to get to those railings, and he slammed on the brakes to avoid hitting them.

I managed to get out of there, but police intelligence later said they usually carried a firearm. So I don't know why they didn't just shoot me.

Did you ever come across police corruption?

Yep. During one job, two of my backup team went off sick. My backup team were not allowed to know my name or where I was from.

When they went off sick, I was introduced to two new cops. I shook the first one's hand and there was no problem at all. With the second one, when I shook his hand, the hairs just went up on the back of my neck. Everything about this guy just seemed wrong.

By this point, I'd been working as an undercover police officer on this particular job for four and a half months, and your senses become really fine-tuned to odd nuance in body language. I told my boss and he removed them both from the briefing.

I didn't think much more of it, but a year later, when police brought down The Gunn Gang, it turned out that the cop I'd taken exception to was an employee of the gang.

He'd been paid to join the police. He was a corrupt cop. He was paid two thousand pounds a month on top of his police wages, plus bonuses for good information.

What was your reaction to that?

Despite being aware of corruption, I was still quite shocked. In the debrief afterwards, I spoke to senior cops and they said,

'Woodsy - we know this happens. With this much money involved, how could it not?'

Did you ever strike up a friendship with a gang member that made their prosecution difficult to deal with?

In that same job, I was under pressure to get evidence about firearms offences. At the time, gangs were at war with each other. There were shootings every day.

It took me four and a half months to get introduced to a gangster that I was very keen to get evidence against. But the person who I manipulated into introducing me to that gangster was a guy called Cammy.

I really liked him, actually. Cammy was a problematic heroin user who'd had a difficult childhood. He was also on bail for dealing heroin, so he was perfect for me to manipulate as he was connected to all of the people I needed.

In total, I think 56 people were eventually arrested. Some decent gangsters, but lots of vulnerable people like Cammy.

Two weeks after the arrests, I heard from the intelligence officer, the guy who kept his ear to the ground. He said that when Cammy was arrested, he was on suicide watch.

The reason for that is that my betrayal of him was the last straw for him. He thought I was the one person in the world he could trust - the one person he could turn to or talk to.

https://twitter.com/JOE_co_uk/status/1324713149338017793?s=20

Surely, that must have spawned an existential crisis where you thought to yourself, 'What am I doing this for?'

Yeah, you know, that just hit me like a ton of bricks.

This nice guy who just... from the circumstances of birth had got into this situation where he had problematic heroin use and not much hope in his life.

I gave up undercover police work after I'd heard that. At least for a few weeks. I thought I was giving it up permanently as it was just too emotionally taxing.

That event, and him becoming suicidal, had made me question everything I had been doing - and all of my decision making.

How did you then get roped back into undercover police work?

A few weeks later, I got a phone call from the detective sergeant who plans all these operations.

He said:

'Woodsy - look, I know you've given this up, but we need you to do this job.

'These gangsters are even worse than the last lot. These gangsters are using gang rape as a reputation-building exercise and to intimidate people. That's as well as kidnapping and maiming.'

How did you convince yourself that you could go back into undercover policing, after what happened with Cammy?

The way I ethically justified it at the time was thinking that 'the end justifies the means'.

Basically, I thought that, yeah I'm causing harm to someone, but the end result is nasty, dangerous gangsters getting put in prison.

Who were this new gang that you were asked to target?

The Burger Bar Boys. They were described to me as the most vicious gang in the country.

One of the gang members was implicated in seven different murders, so these were the kinds of people I was dealing with.

After a few weeks of manipulating street-level dealers, I'll never forget the way I was introduced.

It was at this snooker club where they were holding court. I was directed into the gents' toilets. The door burst open and this hooded figure came in, went into the cubicle, stood on the toilet and looked over the edge.

The door burst open again - and these four hooded figures came in and started walking around me really slowly. Every so often, one of them would headbutt me on the side of the head. Another would punch me in the ribs.

While all this was happening, the guy on the top of the cubicle would look down and ask questions, interrogating me. He'd rephrase certain questions to try and catch me out.

Then, out of nowhere, he just said,

'Okay, what do you want?'

I bought some heroin and crack from him. Over the next couple of months, I ended up buying from all six gang members, which was used against them as evidence of conspiracy to supply class A drugs.

What eventually made you give up undercover policing?

When the penny finally dropped, I realised that with every passing year I did this work, the streets got more and more violent.

I realised a lot of that was down to me, or people like me, using the tactics that I'm using. I had to face up to the fact that there was no benefit to what I was doing.

I took out one gang, and all I did was make another gang happy. Us police are brilliant at catching drug dealers, but that's part of the problem. The next gang that comes in just learn to be more vicious, and they learn the lessons from the last lot that got caught.

Would going after gangsters at the very top of the pyramid reduce crime, rather than targeting street or mid-level dealers?

It doesn't matter what level in the drug market you are - if you remove a player in that drug market, they will be replaced.

From street-level all the way up to international cartel level, it doesn't matter. That's because of the 'Freelancer Effect'.

The way that drugs policing works also creates monopolies. When you take one gang off the streets, that void is then usually filled by the most successful gangsters who aren't already jailed.

When police or the National Crime Agency parade their latest cocaine seizure around, the public are trained to think it's a success. But the size of the drug market has still not been reduced.

Police always talk about a successful drugs raid as having 'disrupted' the market. But, in business circles, the way to create market growth is through market disruption. There are academic papers and even lectures from Richard Branson confirming this.

What is the Freelancer Effect?

I'll give you an example of where I witnessed it. Go back to The Burger Bar Boys in Northampton.

In addition to the evidence gathered against all gang members, we also found out where the supply routes were and who the runners were.

After seven months, I thought we were gonna take down everyone in the town. We got help from five other police forces, and the arrest phase was massive.

A few weeks later, an intelligence officer said to me:

'We managed to interrupt the heroin and crack cocaine supply in Northampton... for a full two hours'.

Seven months of work, almost got myself killed a couple of times, 96 people arrested, all those police resources and all that money just to interrupt the drug supply for two hours.

Another drug gang came in straight away - the Freelancer Effect.

It's noted by police and law enforcement agencies all over the world. They know this.

Wherever there's a gap in the market, crime goes up because people fight over that space. Not only that, drug consumption goes up as well. If you've got two dealers competing for that space, they compete over price, and start doing two-for-one deals.

The only type of crime that can pay for this - and the level of corruption - is the illicit drugs market.

Neil Woods now works as a drug policy reformer. He is part of an international movement of reformers called LEAP (Law Enforcement Action Partnership).

Surveillance photograph of Neil Woods as an undercover police officer, c. 1995.[/caption]

Surveillance photograph of Neil Woods as an undercover police officer, c. 1995.[/caption]

More surveillance footage, c. 1995[/caption]

More surveillance footage, c. 1995[/caption]