Share

2nd February 2018

06:52pm GMT

Elections, referendums, who's hosting predrinks. All are decided on social media where the marginal voters live. When was the last time you picked up the phone? or read the leaflets stuffed through your door? Admittedly that's a campaigning tactic rarely seen in the battle to arrange Ring of Fire but still, when?

An incoming call is probably a PPI robot and I don't attach much literary significance to something easily mistaken for a takeaway menu. That's why social media or, more importantly, data is now integral to corporations, political campaigning and our day-to-day lives.

Smartphones condition our existence. We look at them 150 times a day according to one Facebook executive. App developers build-in satiating methods of interaction, grooving habitual pathways through neurons, tirelessly delivering microdoses of dopamine to our brains.

A man called Loren Brichter invented the pull-to-refresh function for Twitter, social feeds are now replete with his feedback-loop. And while millions of people spend three hours or more a day staring into the black mirror, endlessly refreshing, Loren builds a house in New Jersey, having left Silicon Vally after he became disillusioned with its practices.

Many types of organisation want to capitalise on these new behaviours. It might be Coca Cola wrapping their cans with popular names *uploads to Insta story with the Rio de Janeiro filter.* It might be the Conservative party directing highly targeted ads to a newsfeed because of a user's previously detected sentiment toward stringent financial policy or Brexit. Mind the blood spatters.

Dominic Cummings, the Campaign Director of Vote Leave, is widely credited with extricating Britain from the EU. But he apportions most of his campaign's victory to a once little-known Canadian company called AggregateIQ. They used reams of harvested data to deliver users with laser-guided content.

The Leave campaign spent £3.9 million on AggregateIQ services, more than half its budget and the largest sum of money paid to any company by a campaign during the referendum. Cummings, who estimates his total digital spend as comprising 98 per cent of the overall Vote Leave budget, said: "Without a doubt, the Vote Leave campaign owes a great deal of its success to the work of AggregateIQ. We couldn't have done it without them." They put that quote on the front of their website.

Social media is vitally important to us and our politicians.

Elections, referendums, who's hosting predrinks. All are decided on social media where the marginal voters live. When was the last time you picked up the phone? or read the leaflets stuffed through your door? Admittedly that's a campaigning tactic rarely seen in the battle to arrange Ring of Fire but still, when?

An incoming call is probably a PPI robot and I don't attach much literary significance to something easily mistaken for a takeaway menu. That's why social media or, more importantly, data is now integral to corporations, political campaigning and our day-to-day lives.

Smartphones condition our existence. We look at them 150 times a day according to one Facebook executive. App developers build-in satiating methods of interaction, grooving habitual pathways through neurons, tirelessly delivering microdoses of dopamine to our brains.

A man called Loren Brichter invented the pull-to-refresh function for Twitter, social feeds are now replete with his feedback-loop. And while millions of people spend three hours or more a day staring into the black mirror, endlessly refreshing, Loren builds a house in New Jersey, having left Silicon Vally after he became disillusioned with its practices.

Many types of organisation want to capitalise on these new behaviours. It might be Coca Cola wrapping their cans with popular names *uploads to Insta story with the Rio de Janeiro filter.* It might be the Conservative party directing highly targeted ads to a newsfeed because of a user's previously detected sentiment toward stringent financial policy or Brexit. Mind the blood spatters.

Dominic Cummings, the Campaign Director of Vote Leave, is widely credited with extricating Britain from the EU. But he apportions most of his campaign's victory to a once little-known Canadian company called AggregateIQ. They used reams of harvested data to deliver users with laser-guided content.

The Leave campaign spent £3.9 million on AggregateIQ services, more than half its budget and the largest sum of money paid to any company by a campaign during the referendum. Cummings, who estimates his total digital spend as comprising 98 per cent of the overall Vote Leave budget, said: "Without a doubt, the Vote Leave campaign owes a great deal of its success to the work of AggregateIQ. We couldn't have done it without them." They put that quote on the front of their website.

Social media is vitally important to us and our politicians.

Quantitatively Jeremy Corbyn's digital arms race with Theresa May is a bloody massacre. On Facebook 1.4 million likes plays 455,000. Twitter followers at 1.71 million to 465,000 is no better and qualitative circumstances are more severe.

Jeremy Corbyn's younger socially liberal supporters live for Twitter agg and they don't need a digital toolkit to get retweets. The Conservatives are at risk of becoming the MySpace party in a WhatsApp world. This presents a structural problem to Tory strategists, pivot or lose relevance and the ability to be competitive at a general election. Others have done so with impressive outcomes. The SNP is one such example. During the general election in 2017 the party clocked up 5 million video views and reached more than 10 million people on Facebook. On Twitter they reached 30 million people over the same period. Scotland is inhabited by 5.5 million people.

The party unifies its media, ground game and digital campaigning into one strategy. "Neither is more important than the other and neither takes precedence over the other," digital officer Grant Costello says. "They've all got to be interconnected."

Utter dominance is the result. Three consecutive victories in Scottish elections in the last 10 years, a majority of Westminster's Scottish seats, twice, and more than 400 councillors. One feels the staggering number of votes and likes amassed might be connected.

"Within the first 15 minutes of a video of Ian Blackford during Prime Minister's questions going live, it had more views than the Scottish Lib Dems get in a month. So there is that," Costello jokes.

Election 2017 rallies were live streamed on Facebook. During the party conference that same year the venue's grounds and two main accommodation centres were covered with an "SNP 2017" Snapchat geofilter. They also used the app to remind voters when polls closed, as well as answering policy-based questions from the electorate.

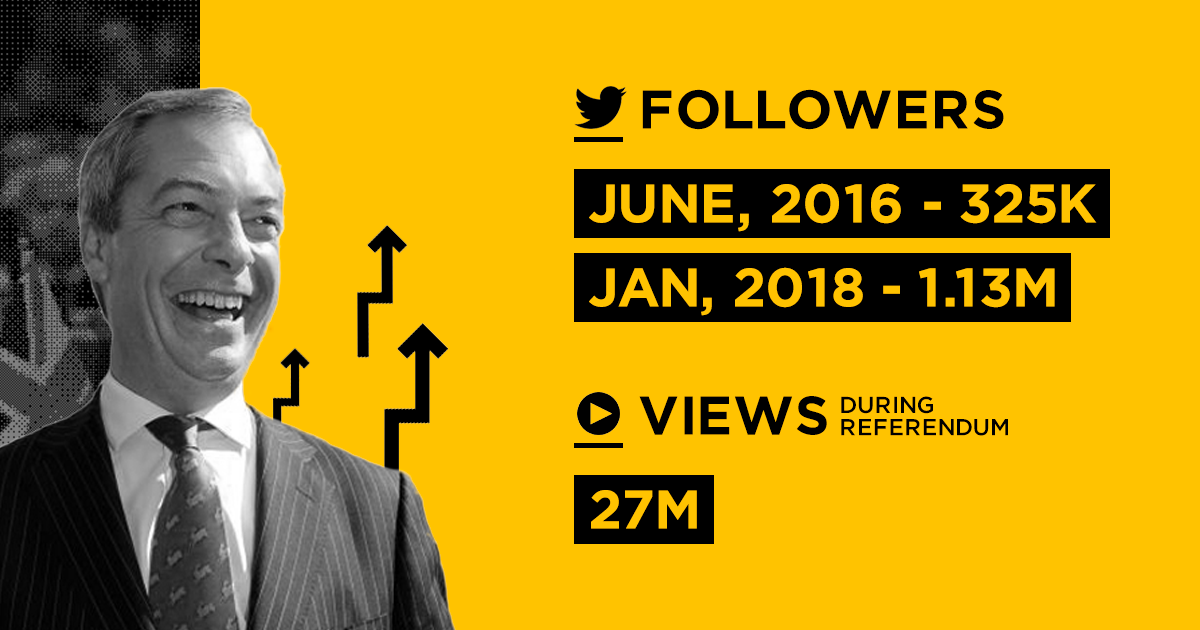

UKIP, and Nigel Farage, have been equally if not more impactful. During the referendum campaign Farage's Facebook page served more than 27 million video views. Since June 24th 2016 the Brexiteer-in-Chief has grown from 325,000 Twitter followers to 1.13 million, endowing him with the second largest online following of any British politician, after Jeremy Corbyn.

"We beat Corbyn most weeks," Dan Jukes says. The 21-year-old has been working on Farage's team for three years and holds the keys to his social accounts. He is revered by party staff for his role in the two-time leader's digital success. UKIP politicians are largely banned from tweeting after four pints by their director of communications, Gawain Towler, to avert ill-advised, inebriated posts. The moratorium doesn't apply to Jukes.

"He is a genius at editing video," Towler tells me. "But there’s also a phenomenal work ethic. Everybody would be out on the piss that evening. Dan would not touch a drop until that video was edited and online, it doesn’t matter how much everyone else was wasted. He would get it done, lock himself away and it would be done."

The SNP is one such example. During the general election in 2017 the party clocked up 5 million video views and reached more than 10 million people on Facebook. On Twitter they reached 30 million people over the same period. Scotland is inhabited by 5.5 million people.

The party unifies its media, ground game and digital campaigning into one strategy. "Neither is more important than the other and neither takes precedence over the other," digital officer Grant Costello says. "They've all got to be interconnected."

Utter dominance is the result. Three consecutive victories in Scottish elections in the last 10 years, a majority of Westminster's Scottish seats, twice, and more than 400 councillors. One feels the staggering number of votes and likes amassed might be connected.

"Within the first 15 minutes of a video of Ian Blackford during Prime Minister's questions going live, it had more views than the Scottish Lib Dems get in a month. So there is that," Costello jokes.

Election 2017 rallies were live streamed on Facebook. During the party conference that same year the venue's grounds and two main accommodation centres were covered with an "SNP 2017" Snapchat geofilter. They also used the app to remind voters when polls closed, as well as answering policy-based questions from the electorate.

UKIP, and Nigel Farage, have been equally if not more impactful. During the referendum campaign Farage's Facebook page served more than 27 million video views. Since June 24th 2016 the Brexiteer-in-Chief has grown from 325,000 Twitter followers to 1.13 million, endowing him with the second largest online following of any British politician, after Jeremy Corbyn.

"We beat Corbyn most weeks," Dan Jukes says. The 21-year-old has been working on Farage's team for three years and holds the keys to his social accounts. He is revered by party staff for his role in the two-time leader's digital success. UKIP politicians are largely banned from tweeting after four pints by their director of communications, Gawain Towler, to avert ill-advised, inebriated posts. The moratorium doesn't apply to Jukes.

"He is a genius at editing video," Towler tells me. "But there’s also a phenomenal work ethic. Everybody would be out on the piss that evening. Dan would not touch a drop until that video was edited and online, it doesn’t matter how much everyone else was wasted. He would get it done, lock himself away and it would be done."

Nigel's output is primarily video-based, using clips from his LBC radio show, regular FOX News appearances or speeches to the European Parliament. A typical view count might be between 1 and 3 million.

Jukes takes a dim view of Conservative digital activity. "Social media is at the heart of what we do. The Conservatives still don’t understand it - they are poor in every way. The right definitely has to work harder online."

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the Green party recognised the need to adapt their campaigning strategy during the 2017 election. A party spokesperson said: ""At the start of the election campaign we had a more traditional campaign strategy, focused on policy announcements and politician visits. But we soon realised this election, like no other in the 21st century so far, was going to be framed as a two-party race. We had to change our approach if we were to breakthrough.

"So we decided to give more staff and financial resources to stunts and social media, and brought in a video producer to capture the results (a first ever for the Green Party). It was a success, and we only wish we had time to make this switch in focus sooner." The Green's best performing post during the election, a clip of Caroline Lucas during one of the leaders debates, reached more than 6 million people.

There are two conflicts taking place in the digital theatre, though. The first's weaponry are views and reach, the second is fought with truth and facts.

Another key aspect of political online messaging is micro-targeted "dark ads."

Facebook allows marketers to pay for adverts to appear in people’s newsfeeds. This is what it is happening when you see "Sponsored" above a post. Rather than sending adverts out to people randomly, it's possible to target people based on certain criteria so the adverts are more relevant. This includes things like location, age, interests, and websites people have visited.

According to Vote Leave campaign director Dominic Cummings, his team delivered "about a billion" such ads during the Brexit referendum. The Electoral Commission are yet to publish 2017's figures, but in 2015 23 per cent of parties' total advertising budget was spent on Facebook ads, a combined £1.3 million. The medium appeals because it is considerably cheaper than, say, newspaper advertising, and reaches far more people.

Following that election, Facebook claimed the Tories had served ads to 80 per cent of the site’s users in key marginal seats. Boasting on its business page: “The party’s videos were viewed 3.5 million times, while 86.9 per cent of all ads served had social context — the all-important endorsement by a friend. Facebook played a vital part in a highly targeted campaign, helping the Conservatives speak to the right people—over and over again.”

For 2017 the Bureau of Investigative Journalism created a sample group of 10,000 users, called Who Targets Me, to share information about political ads directed towards them. The Bureau assessed 7,900 ads from the three major political parties and their leaders that displayed in the sample group’s Facebook feeds. The analysis reveals all three parties posting “dark ads” with tailored campaign messages.

For instance, in the key Conservative target of Ealing Central and Acton, a 65-year-old man saw the following ad.

Nigel's output is primarily video-based, using clips from his LBC radio show, regular FOX News appearances or speeches to the European Parliament. A typical view count might be between 1 and 3 million.

Jukes takes a dim view of Conservative digital activity. "Social media is at the heart of what we do. The Conservatives still don’t understand it - they are poor in every way. The right definitely has to work harder online."

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the Green party recognised the need to adapt their campaigning strategy during the 2017 election. A party spokesperson said: ""At the start of the election campaign we had a more traditional campaign strategy, focused on policy announcements and politician visits. But we soon realised this election, like no other in the 21st century so far, was going to be framed as a two-party race. We had to change our approach if we were to breakthrough.

"So we decided to give more staff and financial resources to stunts and social media, and brought in a video producer to capture the results (a first ever for the Green Party). It was a success, and we only wish we had time to make this switch in focus sooner." The Green's best performing post during the election, a clip of Caroline Lucas during one of the leaders debates, reached more than 6 million people.

There are two conflicts taking place in the digital theatre, though. The first's weaponry are views and reach, the second is fought with truth and facts.

Another key aspect of political online messaging is micro-targeted "dark ads."

Facebook allows marketers to pay for adverts to appear in people’s newsfeeds. This is what it is happening when you see "Sponsored" above a post. Rather than sending adverts out to people randomly, it's possible to target people based on certain criteria so the adverts are more relevant. This includes things like location, age, interests, and websites people have visited.

According to Vote Leave campaign director Dominic Cummings, his team delivered "about a billion" such ads during the Brexit referendum. The Electoral Commission are yet to publish 2017's figures, but in 2015 23 per cent of parties' total advertising budget was spent on Facebook ads, a combined £1.3 million. The medium appeals because it is considerably cheaper than, say, newspaper advertising, and reaches far more people.

Following that election, Facebook claimed the Tories had served ads to 80 per cent of the site’s users in key marginal seats. Boasting on its business page: “The party’s videos were viewed 3.5 million times, while 86.9 per cent of all ads served had social context — the all-important endorsement by a friend. Facebook played a vital part in a highly targeted campaign, helping the Conservatives speak to the right people—over and over again.”

For 2017 the Bureau of Investigative Journalism created a sample group of 10,000 users, called Who Targets Me, to share information about political ads directed towards them. The Bureau assessed 7,900 ads from the three major political parties and their leaders that displayed in the sample group’s Facebook feeds. The analysis reveals all three parties posting “dark ads” with tailored campaign messages.

For instance, in the key Conservative target of Ealing Central and Acton, a 65-year-old man saw the following ad.

The same ad was tweaked for another six key seats, including Westminster North.

The same ad was tweaked for another six key seats, including Westminster North.

Grant Costello of the SNP rightly described digital advertising as a "wilderness" devoid of regulation. Understandable considering there isn't a regulator. When political adverts are placed on TV or other media, they are required by law to disclose who paid for them.

No such legislation exists for digital. The UK's laws aren't applicable online. The closest thing to a watchdog is the Advertising Standards Authority who are not required to regulate political advertising because it's not subject to the Advertising Code. In a statement on their website the regulator said: "The best course of action for anyone with concerns about a political ad is to contact the party responsible and exercise your democratic right to tell them what you think," which is comforting.

The situation has gotten so bad that Facebook itself is trying to remedy the situation, announcing in September last year new rules to prevent political advertising that can’t be traced. The company issued the following statement.

Grant Costello of the SNP rightly described digital advertising as a "wilderness" devoid of regulation. Understandable considering there isn't a regulator. When political adverts are placed on TV or other media, they are required by law to disclose who paid for them.

No such legislation exists for digital. The UK's laws aren't applicable online. The closest thing to a watchdog is the Advertising Standards Authority who are not required to regulate political advertising because it's not subject to the Advertising Code. In a statement on their website the regulator said: "The best course of action for anyone with concerns about a political ad is to contact the party responsible and exercise your democratic right to tell them what you think," which is comforting.

The situation has gotten so bad that Facebook itself is trying to remedy the situation, announcing in September last year new rules to prevent political advertising that can’t be traced. The company issued the following statement.

Going forward—and perhaps the most important step we're taking—we're going to make political advertising more transparent. Not only will you have to disclose which page paid for an ad, but we will also make it so you can visit an advertiser's page and see the ads they're currently running to any audience on Facebook. We will roll this out over the coming months, and we will work with others to create a new standard for transparency in online political ads.No conflict of interest there.

Tom Hegarty works for Full Fact, a fact checking organisation that assesses the truth of statements made by parties and their politicians. Over lunch he lamented to me about the lack of a digital regulator and the resultant culture the situation has fostered. A lot of Full Fact's work now focuses on social media and the validity of claims made on it.

Facebook donated £50,000 of advertising credits to the charity to support their work during the general election. One of their fact-checks was shared more than 12,000 times, with virality comparable to the original meme it disproved.

The Full Fact team fact-checked claims made in each of the six major parties' manifesto launches, publishing 100 new fact-checks and eight explainers during the eight week period of the snap election. They also live fact-checked the seven leaders debates. A rough summary, no one is telling the truth.

Tom Hegarty works for Full Fact, a fact checking organisation that assesses the truth of statements made by parties and their politicians. Over lunch he lamented to me about the lack of a digital regulator and the resultant culture the situation has fostered. A lot of Full Fact's work now focuses on social media and the validity of claims made on it.

Facebook donated £50,000 of advertising credits to the charity to support their work during the general election. One of their fact-checks was shared more than 12,000 times, with virality comparable to the original meme it disproved.

The Full Fact team fact-checked claims made in each of the six major parties' manifesto launches, publishing 100 new fact-checks and eight explainers during the eight week period of the snap election. They also live fact-checked the seven leaders debates. A rough summary, no one is telling the truth.

Explore more on these topics:

Politics - JOE.co.uk | Joe.co.uk

politics