Share

27th April 2021

05:57pm BST

Liam Byrne at his campaign office in Birmingham city centre (Credit: Nadine Batchelor-Hunt)[/caption]

He is up against Conservative incumbent and former businessman Andy Street, who won the 2017 mayoral election by around 4,000 votes.

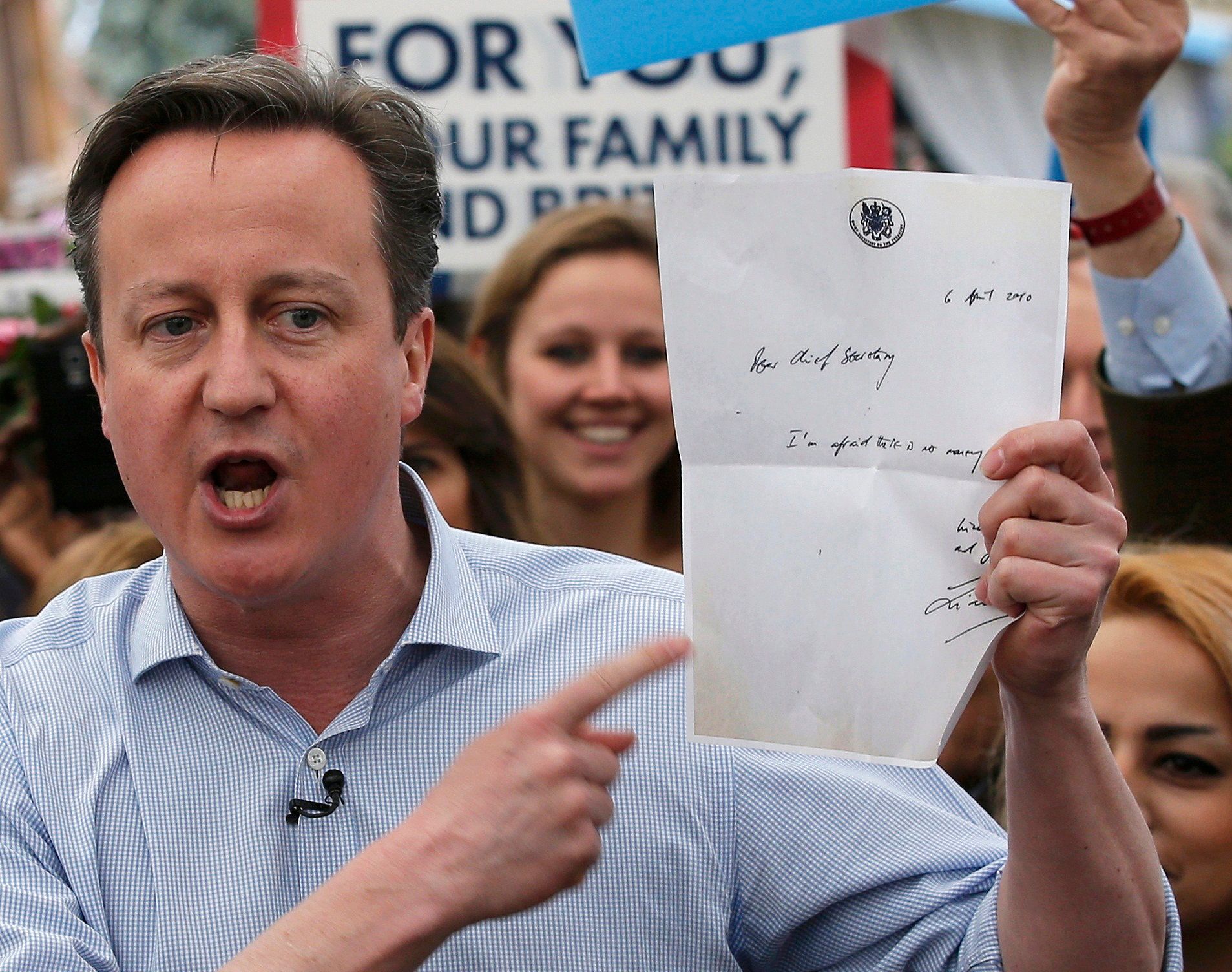

First elected as an MP in 2004, serving in the cabinet under Gordon Brown as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Liam Byrne notoriously left a note to his successor which said "I’m afraid there is no money" when Labour lost the 2010 general election. He afterwards said it was one of his greatest regrets, as it was used a stick to hit Labour with at the next General Election.

Not that anyone needs reminding, but since then Labour has not had so much as a taste of the leftovers of government, slumping to their worst electoral performance in nearly a hundred years in 2019.

[caption id="attachment_271235" align="alignnone" width="1907"]

Liam Byrne at his campaign office in Birmingham city centre (Credit: Nadine Batchelor-Hunt)[/caption]

He is up against Conservative incumbent and former businessman Andy Street, who won the 2017 mayoral election by around 4,000 votes.

First elected as an MP in 2004, serving in the cabinet under Gordon Brown as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Liam Byrne notoriously left a note to his successor which said "I’m afraid there is no money" when Labour lost the 2010 general election. He afterwards said it was one of his greatest regrets, as it was used a stick to hit Labour with at the next General Election.

Not that anyone needs reminding, but since then Labour has not had so much as a taste of the leftovers of government, slumping to their worst electoral performance in nearly a hundred years in 2019.

[caption id="attachment_271235" align="alignnone" width="1907"] David Cameron holding Liam Byrne's "there's no money left" note during an election rally in 2015 (Credit: Getty)[/caption]

On why exactly this happened, Byrne was initially vague, but said the key issues were Corbyn and Brexit, as well as a gradual shift away from Labour among its base support.

"I think it was those two things, but I think there was also a kind of 'what are you for?', 'where are you going?'," he said.

David Cameron holding Liam Byrne's "there's no money left" note during an election rally in 2015 (Credit: Getty)[/caption]

On why exactly this happened, Byrne was initially vague, but said the key issues were Corbyn and Brexit, as well as a gradual shift away from Labour among its base support.

"I think it was those two things, but I think there was also a kind of 'what are you for?', 'where are you going?'," he said.

"I heard, literally time and time again: Brexit, Jeremy, Jeremy, Brexit.

"But underneath that, you can sense that this was not some kind of new break, people were drifting from us for a while - and that is because they’d lost a sense of what we were for."

He's not wrong; Labour's rot in the West Midlands set in decades ago: in 2001, the Conservatives had just four seats out of the 28 up for grabs in the West Midlands area - in 2021, they have half. Furthermore, Byrne finds himself up against an incumbent Conservative mayor. So what are Labour for? The party have come under harsh criticism during the pandemic for failing to provide strong opposition, with many criticising the party's frequent abstentions, like leader Sir Keir Starmer's decision to equivocate on the controversial covert human intelligence sources bill.And, despite having a boost in the polls at the beginning of Starmer's leadership, Labour are once again behind the Conservatives.Spycops, cannabis, behind in the polls. How many of our questions did Keir Starmer answer? pic.twitter.com/jVxTEv1Nsl

— PoliticsJOE (@PoliticsJOE_UK) April 22, 2021

Byrne claims his mayoral campaign has been "laser targeted," contacting a pool of 600,000 people to get their input on "their ambitions and anxieties", as well as their "hopes" and "dreams", to address the votes Labour are haemorrhaging.

"The people who have come together around this campaign, are people who all believe that our performance doesn’t match our potential, and they’re sick of it," Byrne said.

"It’s a coalition of people who want to win this election, but also win this election in a way that bends the future of the Labour Party."

Since our interview, polling emerged in The Times placing Byrne behind opponent Andy Street by almost ten points. We went back to his team for comment but they declined, and directed us to approach Labour HQ, who also declined to comment.According to his manifesto, Byrne's campaign’s key goals centre around seven pledges that include "lead green Britain," "bring back industry," "build more homes," and "support our youth".

Birmingham has the youngest population of any European city. He says part of his plan is green industry zones on brownfield sites across the region, focusing on renewable power, batteries, and access to "green skill." They aim to create 200,000 jobs, in part attached to the Commonwealth Games 2022 and construction, which they believe will help tackle the West Midlands' high levels of poverty. The issue of poverty is likely to feel very personal as his own constituency, Birmingham Hodge Hill, was labelled the most deprived in the West Midlands metro area in 2019. Tram in Birmingham City Centre (Via Getty)[/caption]

And, as I drove into Birmingham town centre to meet Byrne, the congestion and traffic jams on the roads - still in the midst of a semi-lockdown - were yet another reminder of how desperately transport infrastructure needs an overhaul.

In 2017 the World Health Organisation said air pollution levels in the West Midlands were higher than guidelines suggest.

Byrne criticised Street's slow progress on extending tram lines, saying if Labour won the mayoral race he'd seek to build a swifter and more cost efficient "very light rail".

He also criticised how far behind the West Midlands area is compared to the capital, and other metro areas like Manchester, insisting the region deserved better.

Tram in Birmingham City Centre (Via Getty)[/caption]

And, as I drove into Birmingham town centre to meet Byrne, the congestion and traffic jams on the roads - still in the midst of a semi-lockdown - were yet another reminder of how desperately transport infrastructure needs an overhaul.

In 2017 the World Health Organisation said air pollution levels in the West Midlands were higher than guidelines suggest.

Byrne criticised Street's slow progress on extending tram lines, saying if Labour won the mayoral race he'd seek to build a swifter and more cost efficient "very light rail".

He also criticised how far behind the West Midlands area is compared to the capital, and other metro areas like Manchester, insisting the region deserved better.

Byrne also says his campaign is part of Labour "rediscovering the lost soul" away from the “technocratic blah-de-blah of day-to-day Westminster politics.”

However, while he may want to separate the election from Westminster, the state of the parliamentary Labour party and its leader will undoubtably have a direct impact on how voters behave at the polls - which is bad news for him. Labour are behind the Conservatives by a considerable margin, and Starmer's popularity as leader has tanked among the public, with a recent YouGov poll suggesting that just 26 per cent people thinking he's doing a good job. However, there is a chance they may be shown some reprieve, as Labour's accusations of "Tory sleaze" - following a string of scandals in the party over the last several weeks - may have eaten into their lead. A recent Ipsos Mori poll suggests that the Conservative lead has fallen by five points. While this may be good news for Labour, Byrne's campaign is coming under attack from sections of the media with allegations of discrepancies in campaign expenses. The latter allegation was reported following this interview by Guido Fawkes and Skwawkbox. When JOE approached Byrne's team for comment, the Labour party press office responded with a statement strongly denying the allegations and confirming that they are not investigating it, adding: "All expenses are recorded in line with [Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority] regulations and all campaign donations are within the rules and will be reported in the usual way." [caption id="attachment_270580" align="alignnone" width="2048"] (Credit: Getty)[/caption]

On Starmer's leadership, Byrne was positive.

"Keir's leadership is strong, competent, and he treasures local government," he said

"He knows that it was a shocking defeat in December 2019 and, you know, when you're trying to rebuild after a defeat, that is big - you've got to rebuild from the grassroots up."

"He doesn't underestimate the scale of the task and the scale of the mountain."

Despite this, when asked if he believed Labour as a party needed to have a clearer vision and clearer principles in the way he says his West Midlands mayoral campaign has, he said yes.

(Credit: Getty)[/caption]

On Starmer's leadership, Byrne was positive.

"Keir's leadership is strong, competent, and he treasures local government," he said

"He knows that it was a shocking defeat in December 2019 and, you know, when you're trying to rebuild after a defeat, that is big - you've got to rebuild from the grassroots up."

"He doesn't underestimate the scale of the task and the scale of the mountain."

Despite this, when asked if he believed Labour as a party needed to have a clearer vision and clearer principles in the way he says his West Midlands mayoral campaign has, he said yes.

“Yeah - we talk to Keir’s office and MPs a lot about this,” he said.

"We talk about this stuff all the time because there probably isn't another part of the Labour movement that's doing the level of research that we are."Byrne is also calling for a greater political alliance of regional mayors to take on Westminster politics, to get what he believes is the fair share of funding for regions outside of London.

“I think there's real power in the Labour mayors coming together to say, you know what, too much money is stuck in London, and it's time to now start moving resources out.”

[caption id="attachment_271244" align="alignnone" width="2048"] The Birmingham Bull (Credit: Getty)[/caption]

He praised Andy Burnham's leadership as Manchester mayor for being outspoken, particularly during the pandemic.

Burnham gained notoriety last year after taking on the government for a better package of financial support for the North after it experienced harsher and longer restrictions than the rest of the country.

It is by this metric that Byrne says his opponent is not ambitious enough.

"Andy Street has basically said 'thank you very much' when he gets breadcrumbs thrown at him, he's not ambitious enough for the region," he said.

"He had a decent relationship with Theresa May, he has a terrible relationship with Boris Johnson, but he's got a couple of problems.

"So one, is that he lacks the political craft skills to bring people together but second, he's got this ambivalent relationship with the Conservative party."

At this point, Byrne's press officer forwarded pictures of Street's campaign leaflets - which are green instead of blue, and appear to have the Conservative party logo in small writing. Byrne's campaign have repeatedly expressed frustration that Street's marketing doesn't show clearly enough which party he is representing.

[caption id="attachment_271234" align="alignnone" width="900"]

The Birmingham Bull (Credit: Getty)[/caption]

He praised Andy Burnham's leadership as Manchester mayor for being outspoken, particularly during the pandemic.

Burnham gained notoriety last year after taking on the government for a better package of financial support for the North after it experienced harsher and longer restrictions than the rest of the country.

It is by this metric that Byrne says his opponent is not ambitious enough.

"Andy Street has basically said 'thank you very much' when he gets breadcrumbs thrown at him, he's not ambitious enough for the region," he said.

"He had a decent relationship with Theresa May, he has a terrible relationship with Boris Johnson, but he's got a couple of problems.

"So one, is that he lacks the political craft skills to bring people together but second, he's got this ambivalent relationship with the Conservative party."

At this point, Byrne's press officer forwarded pictures of Street's campaign leaflets - which are green instead of blue, and appear to have the Conservative party logo in small writing. Byrne's campaign have repeatedly expressed frustration that Street's marketing doesn't show clearly enough which party he is representing.

[caption id="attachment_271234" align="alignnone" width="900"] Andy Street campaign leaflet (Credit: Oliver Longworth)[/caption]

Andy Street campaign leaflet (Credit: Oliver Longworth)[/caption]